Minimum phase

In control theory and signal processing, a linear, time-invariant system is said to be minimum-phase if the system and its inverse are causal and stable.[1][2]

For example, a discrete-time system with rational transfer function  can only satisfy causality and stability requirements if all of its poles are inside the unit circle. However, we are free to choose whether the zeros of the system are inside or outside the unit circle. A system is minimum-phase if all its zeros are also inside the unit circle. Insight is given below as to why this system is called minimum-phase.

can only satisfy causality and stability requirements if all of its poles are inside the unit circle. However, we are free to choose whether the zeros of the system are inside or outside the unit circle. A system is minimum-phase if all its zeros are also inside the unit circle. Insight is given below as to why this system is called minimum-phase.

Contents |

Inverse system

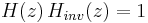

A system  is invertible if we can uniquely determine its input from its output. I.e., we can find a system

is invertible if we can uniquely determine its input from its output. I.e., we can find a system  such that if we apply

such that if we apply  followed by

followed by  , we obtain the identity system

, we obtain the identity system  . (See Inverse matrix for a finite-dimensional analog). I.e.,

. (See Inverse matrix for a finite-dimensional analog). I.e.,

Suppose that  is input to system

is input to system  and gives output

and gives output  .

.

Applying the inverse system  to

to  gives the following.

gives the following.

So we see that the inverse system  allows us to determine uniquely the input

allows us to determine uniquely the input  from the output

from the output  .

.

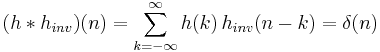

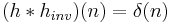

Discrete-time example

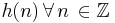

Suppose that the system  is a discrete-time, linear, time-invariant (LTI) system described by the impulse response

is a discrete-time, linear, time-invariant (LTI) system described by the impulse response  . Additionally,

. Additionally,  has impulse response

has impulse response  . The cascade of two LTI systems is a convolution. In this case, the above relation is the following:

. The cascade of two LTI systems is a convolution. In this case, the above relation is the following:

where  is the Kronecker delta or the identity system in the discrete-time case. Note that this inverse system

is the Kronecker delta or the identity system in the discrete-time case. Note that this inverse system  is not unique.

is not unique.

Minimum phase system

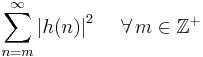

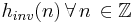

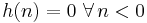

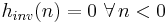

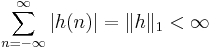

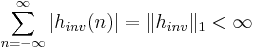

When we impose the constraints of causality and stability, the inverse system is unique; and the system  and its inverse

and its inverse  are called minimum-phase. The causality and stability constraints in the discrete-time case are the following (for time-invariant systems where h is the system's impulse response):

are called minimum-phase. The causality and stability constraints in the discrete-time case are the following (for time-invariant systems where h is the system's impulse response):

Causality

and

Stability

and

See the article on stability for the analogous conditions for the continuous-time case.

Frequency analysis

Discrete-time frequency analysis

Performing frequency analysis for the discrete-time case will provide some insight. The time-domain equation is the following.

Applying the Z-transform gives the following relation in the z-domain.

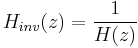

From this relation, we realize that

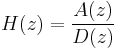

For simplicity, we consider only the case of a rational transfer function H (z). Causality and stability imply that all poles of H (z) must be strictly inside the unit circle (See stability). Suppose

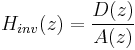

where A (z) and D (z) are polynomial in z. Causality and stability imply that the poles – the roots of D (z) – must be strictly inside the unit circle. We also know that

So, causality and stability for  imply that its poles – the roots of A (z) – must be inside the unit circle. These two constraints imply that both the zeros and the poles of a minimum phase system must be strictly inside the unit circle.

imply that its poles – the roots of A (z) – must be inside the unit circle. These two constraints imply that both the zeros and the poles of a minimum phase system must be strictly inside the unit circle.

Continuous-time frequency analysis

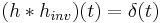

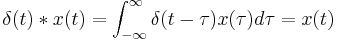

Analysis for the continuous-time case proceeds in a similar manner except that we use the Laplace transform for frequency analysis. The time-domain equation is the following.

where  is the Dirac delta function. The Dirac delta function is the identity operator in the continuous-time case because of the sifting property with any signal x (t).

is the Dirac delta function. The Dirac delta function is the identity operator in the continuous-time case because of the sifting property with any signal x (t).

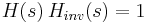

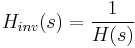

Applying the Laplace transform gives the following relation in the s-plane.

From this relation, we realize that

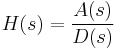

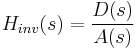

Again, for simplicity, we consider only the case of a rational transfer function H(s). Causality and stability imply that all poles of H (s) must be strictly inside the left-half s-plane (See stability). Suppose

where A (s) and D (s) are polynomial in s. Causality and stability imply that the poles – the roots of D (s) – must be inside the left-half s-plane. We also know that

So, causality and stability for  imply that its poles – the roots of A (s) – must be strictly inside the left-half s-plane. These two constraints imply that both the zeros and the poles of a minimum phase system must be strictly inside the left-half s-plane.

imply that its poles – the roots of A (s) – must be strictly inside the left-half s-plane. These two constraints imply that both the zeros and the poles of a minimum phase system must be strictly inside the left-half s-plane.

Relationship of magnitude response to phase response

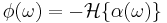

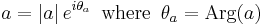

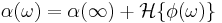

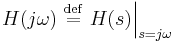

A minimum-phase system, whether discrete-time or continuous-time, has an additional useful property that the natural logarithm of the magnitude of the frequency response (the "gain" measured in nepers which is proportional to dB) is related to the phase angle of the frequency response (measured in radians) by the Hilbert transform. That is, in the continuous-time case, let

be the complex frequency response of system H(s). Then, only for a minimum-phase system, the phase response of H(s) is related to the gain by

and, inversely,

![\log \left( |H(j \omega)| \right) = \log \left( |H(j \infty)| \right) %2B \mathcal{H} \lbrace \arg \left[H(j \omega) \right] \rbrace \](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4b5cf913cd08a05a970dda45edff65dd.png) .

.

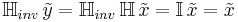

Stated more compactly, let

where  and

and  are real functions of a real variable. Then

are real functions of a real variable. Then

and

.

.

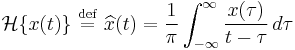

The Hilbert transform operator is defined to be

.

.

An equivalent corresponding relationship is also true for discrete-time minimum-phase systems.

Minimum phase in the time domain

For all causal and stable systems that have the same magnitude response, the minimum phase system has its energy concentrated near the start of the impulse response. i.e., it minimizes the following function which we can think of as the delay of energy in the impulse response.

Minimum phase as minimum group delay

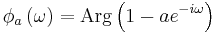

For all causal and stable systems that have the same magnitude response, the minimum phase system has the minimum group delay. The following proof illustrates this idea of minimum group delay.

Suppose we consider one zero  of the transfer function

of the transfer function  . Let's place this zero

. Let's place this zero  inside the unit circle (

inside the unit circle ( ) and see how the group delay is affected.

) and see how the group delay is affected.

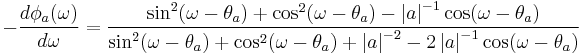

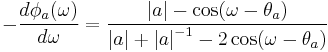

Since the zero  contributes the factor

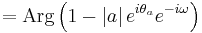

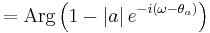

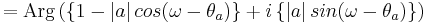

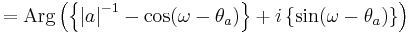

contributes the factor  to the transfer function, the phase contributed by this term is the following.

to the transfer function, the phase contributed by this term is the following.

contributes the following to the group delay.

contributes the following to the group delay.

The denominator and  are invariant to reflecting the zero

are invariant to reflecting the zero  outside of the unit circle, i.e., replacing

outside of the unit circle, i.e., replacing  with

with  . However, by reflecting

. However, by reflecting  outside of the unit circle, we increase the magnitude of

outside of the unit circle, we increase the magnitude of  in the numerator. Thus, having

in the numerator. Thus, having  inside the unit circle minimizes the group delay contributed by the factor

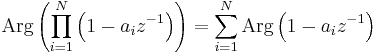

inside the unit circle minimizes the group delay contributed by the factor  . We can extend this result to the general case of more than one zero since the phase of the multiplicative factors of the form

. We can extend this result to the general case of more than one zero since the phase of the multiplicative factors of the form  is additive. I.e., for a transfer function with

is additive. I.e., for a transfer function with  zeros,

zeros,

So, a minimum phase system with all zeros inside the unit circle minimizes the group delay since the group delay of each individual zero is minimized.

Non-minimum phase

Systems that are causal and stable whose inverses are causal and unstable are known as non-minimum-phase systems. A given non-minimum phase system will have a greater phase contribution than the minimum-phase system with the equivalent magnitude response.

Maximum phase

A maximum-phase system is the opposite of a minimum phase system. A causal and stable LTI system is a maximum-phase system if its inverse is causal and unstable. That is,

- The zeros of the discrete-time system are outside the unit circle.

- The zeros of the continuous-time system are in the right-hand side of the complex plane.

Such a system is called a maximum-phase system because it has the maximum group delay of the set of systems that have the same magnitude response. In this set of equal-magnitude-response systems, the maximum phase system will have maximum energy delay.

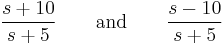

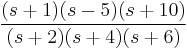

For example, the two continuous-time LTI systems described by the transfer functions

have equivalent magnitude responses; however, the first system has a much larger contribution to the phase shift. Hence, in this set, the second system is the maximum-phase system and the first system is the minimum-phase system.

Mixed phase

A mixed-phase system has some of its zeros inside the unit circle and has others outside the unit circle. Thus, its group delay is neither minimum or maximum but somewhere between the group delay of the minimum and maximum phase equivalent system.

For example, the continuous-time LTI system described by transfer function

is stable and causal; however, it has zeros on both the left- and right-hand sides of the complex plane. Hence, it is a mixed-phase system.

Linear phase

A linear-phase system has constant group delay. Non-trivial linear phase or nearly linear phase systems are also mixed phase.

See also

- All-pass filter – A special non-minimum-phase case.

- Kramers–Kronig relation – Minimum phase system in physics

References

- ^ Hassibi, Babak; Kailath, Thomas; Sayed, Ali H. (2000). Linear estimation. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. pp. 193. ISBN 0-13-022464-2.

- ^ J. O. Smith III, Introduction to Digital Filters with Audio Applications (September 2007 Edition).

Further reading

- Dimitris G. Manolakis, Vinay K. Ingle, Stephen M. Kogon : Statistical and Adaptive Signal Processing, pp. 54-56, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-040051-2

- Boaz Porat : A Course in Digital Signal Processing, pp. 261-263, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-14961-6

![\arg \left[ H(j \omega) \right] = -\mathcal{H} \lbrace \log \left( |H(j \omega)| \right) \rbrace \](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c97b165b0ea56613807ad1f1b1ee2791.png)

![H(j \omega) = |H(j \omega)| e^{j \arg \left[H(j \omega) \right]} \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ e^{\alpha(\omega)} e^{j \phi(\omega)} = e^{\alpha(\omega) %2B j \phi(\omega)} \](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cc6ea7eff322e65c81f44a5623ae6f8f.png)